Gonzales Flag: Meaning and History Behind "Come and Take It"

You're free to republish or share any of our articles (either in part or in full), which are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Our only requirement is that you give Ammo.com appropriate credit by linking to the original article. Spread the word; knowledge is power!

“Come and Take It.” It’s a slogan of defiance against government tyranny with roots in antiquity that continues to inspire freedom-loving patriots today. This updating of the classic Spartan molṑn labé (meaning “come and take them”) is a powerful challenge to would-be gun grabbers. Seeking to remove arms from the people will not come without dear cost. For the Texian rebels of the Battle of Gonzales, these words were not mere tough talk. They were words the Texians were willing to die for.

“Come and Take It.” It’s a slogan of defiance against government tyranny with roots in antiquity that continues to inspire freedom-loving patriots today. This updating of the classic Spartan molṑn labé (meaning “come and take them”) is a powerful challenge to would-be gun grabbers. Seeking to remove arms from the people will not come without dear cost. For the Texian rebels of the Battle of Gonzales, these words were not mere tough talk. They were words the Texians were willing to die for.

Enter The Gonzales Battle Flag

The story begins in 1831. Texians in Gonzales, then a part of Mexico, requested a cannon from federal authorities to defend themselves from Comanche raids. The cannon itself was of little military use (historian Timothy Todish once said it wasn’t good for much more than starting horse races). Indeed, it probably served more as a visual deterrent to the hostile natives than a military one.

Curiously, Gonzales was one the communities preferring Mexican rule to independence, even after relations between Mexico and the Texians began to sour. The town went so far as to declare their allegiance to the Mexican government of Santa Anna. However, on September 10, 1835, a Mexican soldier beat a Gonzales Texian, sparking widespread outrage. It was after this incident that the federal government thought it best to retrieve the cannon before it was turned on the Mexican government.

Supreme commander of the Mexican military, Colonel Domingo de Ugartechea, sent out Corporal Casimiro De León and five soldiers of the Second Flying Company of San Carlos de Parras. Emboldened by other Mexican states in open revolt, the Texians refused to return the weapon, taking De León and his men hostage. Ultimately, it wasn’t about the cannon. The Texians were worried that the Mexican government planned to use recent unrest to disband local militias, which the Texians considered absolutely essential for freedom and safety.

Texians decided to bury the cannon in George W. Davis's peach orchard. This and other methods of subterfuge delayed the arrival of 100 Mexican dragoons. By the time they arrived, Texians had amassed a force 140 strong. On October 1, 1835, these men voted and decided that if the Mexican government wanted their cannon back, they were going to have to fight for it. The simple refusal to surrender the cannon acted as the spark that ignited the wildfire of the Texas Revolution.

Gonzales Flag Meaning

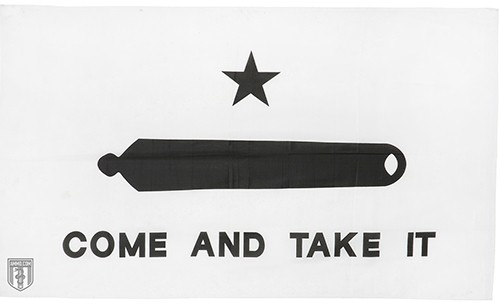

The Gonzales Flag is a stark black-and-white banner, a simple design that acted as a stark gauntlet thrown at the feet of Mexican federal power. It was nothing more than a star, the cannon in question and the old Spartan slogan updated for modern times: “Come and Take It.”

It’s not clear that the Texian freedom fighters knew they were echoing the words spoken at the dawn of Western freedom. On October 2, when Lieutenant Castañeda requested that the cannon be returned under the terms of the original agreement, the Texians simply pointed to the weapon sitting 200 yards behind them saying, “There it is. Come and take it.” Once armed conflict began between the settlers and the Mexican federals, Texian community leaders commissioned a flag from local ladies to fly over the cannon. “Come and Take It” was both a cry of freedom and a taunt to tyrants.

Texians didn’t wait for an attack, but rather went on an offensive of their own, using the cannon. They had nothing in the way of cannon balls. Instead, scrap metal was used as mortar to fire at the oncoming Mexican forces. James C. Neill, a War of 1812 veteran, was given command of Texas’ first artillery regiment. The local Methodist minister gave the assault his blessing, invoking the Spirit of 1776. The Texians also swore loyalty to another constitution – the Mexican one of 1824, which Santa Anna had repudiated in favor of greater centralized control. The commanding officer of Mexican forces, ironically, was in ideological solidarity with the settlers, but his first duty was as a soldier.

When all was said and done, this minor battle, lasting only a few hours, forced the retreat of Mexican forces. Two Mexican soldiers died. The only Texian casualty was a man thrown from his horse who suffered a bloody nose. The Battle of Gonzales represented a final and definitive break between Texian settlers and the Mexican government. There would be no going back to business as usual. Word of the battle quickly spread through the United States, where the event (initially known merely as "the fight at Williams' place") was lionized as “the Lexington of Texas.” Young men flocked to Texas to join the cause of freedom against military despotism.

Thousands of Texians had taken an armed posture that they couldn’t walk back from. Stephen F. Austin, long first among equals and the most respected Texian, became the Father of His Country after this battle. The Texian militia unanimously elected Austin as their leader. He had no military training, but quickly led the men on an assault on Mexican forces. By the end of 1835, all Mexican forces had been driven out of Texas.

No one is sure what happened to that cannon, but the words on the flag continue to resonate today, particularly within the pro-Second Amendment movement. In the 1980s, one enterprising soul replaced the cannon with an M16A12 rifle, waving the banner at a Bill of Rights rally in Arizona. In 2002, the flag first appeared with a Barret .50 BMG Rifle.

That the slogan of Spartan warriors would resonate with Texian forces thousands of years later, shows just how powerful an idea this is: Tyrants who wish to disarm a free people will get a fight.

Flags

- Gonzales Flag: Meaning and History Behind "Come and Take It"

- The Fort Moultrie Flag: Southern Liberty During the American Revolution

- The Gadsden Flag History: Don't Tread On Me and the Gadsden Flag Meaning

- The Bennington Flag: A Pre-Constitutional Symbol of Freedom

- The Molon Labe Flag: Come and Take Them and the Ancient History of Modern Liberty

- Betsy Ross Flag: 5 Betsy Ross Flag Facts You Might Not Know and Their History

- Navy Jack Flag: History of the First Navy Jack and The Ultimate Symbol of Freedom

- The Sons of Liberty Flag: How The Rebellious Stripes Flag Shaped American Patriotism

- Don't Give Up the Ship: How The Commodore Perry Flag Inspired American Bravery & Tenacity

- The Culpeper Minutemen Flag: The History of the Banner Flown by a Militia of Patriots

- Bedford Flag History: Vince Aut Morire - The Forgotten History of The Conquer or Die Flag