Roof Koreans: How Civilians Defended Koreatown from Racist Violence During the 1992 LA Riots

You're free to republish or share any of our articles (either in part or in full), which are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Our only requirement is that you give Ammo.com appropriate credit by linking to the original article. Spread the word; knowledge is power!

The riots of the spring of 2020 are far from without precedent in the United States. Indeed, they seem to happen once a generation at least. The 1992 Los Angeles Riots are such an example of these “generational riots.” And while most people know about the riots, less known – though quite well known at the time – were the phenomenon of the so-called “Roof Koreans.”

The riots of the spring of 2020 are far from without precedent in the United States. Indeed, they seem to happen once a generation at least. The 1992 Los Angeles Riots are such an example of these “generational riots.” And while most people know about the riots, less known – though quite well known at the time – were the phenomenon of the so-called “Roof Koreans.”

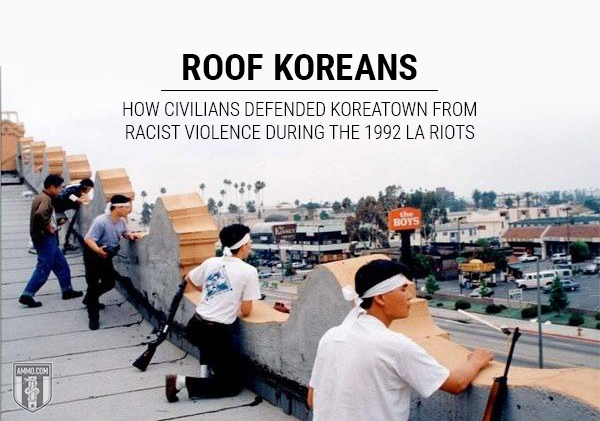

The Roof Koreans were spontaneous self-defense forces organized by the Korean community of Los Angeles, primarily centered in Koreatown, in response to violent and frequently racist attacks on their communities and businesses by primarily black looters and rioters during the Los Angeles Riots of 1992. Despite their best efforts, over 2,200 Korean-owned businesses were looted or burned to the ground during the riots. It is chilling to imagine how many would have suffered the same fate had the Koreans not been armed.

Standing on the rooftops of Koreatown shops they and their families owned, clad not in body armor or tactical gear, but instead dressed like someone’s nerdy dad, often smoking cigarettes, but always on alert, the Roof Koreans provide a stirring example of how free Americans of all races can defend their own communities without relying upon outside help.

The Koreans of Los Angeles were the ultimate marginalized minority group. They were subject to discrimination and often victimized by the black community of the city. Due to language barriers and other factors, they lacked the political clout of other minority groups, such as the large Mexican community of Los Angeles County. This in spite of their clear economic success in the city beginning in the 1970s and 80s.

The reasons for the tensions between the Korean and black communities of Los Angeles pre-dates the riots, which were largely just the match that ignited the powder keg that had been this region of Los Angeles for years. To understand what happened in Koreatown in 1992, it is necessary to understand much more than simply the Rodney King trial and the resulting riots.

The Roots of Korean Business Ownership in Black Communities

How is it that the Korean-American community of Los Angeles ended up owning so much property in what were largely black neighborhoods? The answer, ironically, lies in a previous riot, the Watts Riot of 1965. This riot, which included six full days of arson and looting, was kicked off when a black man was arrested for drunk driving.

The riots occurred roughly at the same time that the Koreans started showing up in America. This meant that, among other things, businesses and real estate were very cheap to purchase. The newly arrived Korean immigrants began buying up the businesses that no one else wanted. By the 1980s, it wasn’t limited to Los Angeles – Koreans were dominating the mom-and-pop shops from coast to coast. But the resentment in the City of Angels was growing.

Prologue: The Death of Latasha Harlins

While it was not the start of tensions in the city between these two communities, the killing of Latasha Harlins in 1991 certainly ratcheted the situation up to a new level.

While it was not the start of tensions in the city between these two communities, the killing of Latasha Harlins in 1991 certainly ratcheted the situation up to a new level.

Harlins, whose personal life is a hard-luck story that does not bear repeating here, was 15 at the time when she was shot and killed by Korean shopkeeper Soon Ja Du, a 51-year-old woman born in Korea. Du generally didn’t even work in the store, a task that typically fell on her husband and her son. However, that day she was covering for her husband who was outside in the family’s van.

Du claimed that Harlins was trying to steal a $1.79 bottle of orange juice, but witnesses said they heard Du call Harlins a slur and heard Harlins say she planned to pay for the juice, with money in hand. After reviewing video tape footage, the police agreed with the witnesses. Video footage further showed Du grabbing Harlins by her sweatshirt and backpack.

Harlins responded by striking Du twice, which knocked the latter to the ground. Harlins started to back away, prompting Du to throw a stool at her. The two struggled over the juice before Harlins went to leave. Du went behind the counter and grabbed a revolver, firing at a retreating Harlins from behind from three feet away. Harlins was killed instantly by a bullet to the back of the head.

Billy Heung Ki Du, Ja’s husband, rushed into the store after hearing the gunshot. His wife asked where Harlins was before she fainted. Mr. Du then called 911 to report an attempted holdup.

Mrs. Du was charged with voluntary manslaughter, a charge that can carry up to 16 years in prison. At trial, she testified on her own behalf. The jury recommended the maximum sentence, which the judge rejected, instead giving Mrs. Du time served, five years probation, 500 hours of community service and a $500 fine. The California Court of Appeals upheld the sentence about a week before the riots began in a unanimous decision. Harlins’ family received a settlement of $300,000.

The case wasn’t the first example of tensions between the two communities, but it was a microcosm for them and perhaps the worst from an optics perspective. In 1991, the Los Angeles Times reported that there were four shootings in the span of just over four months involving a Korean shooter and a black target. The store was eventually burned down during the riots, never to reopen.

That same year, there was an over 100-day boycott of a Korean-American-owned liquor store that ended when the owner was effectively bullied into selling his store to a black owner. Then-Mayor Tom Bradley, who many blamed for the riots, was instrumental in coming to this “settlement” which chased a Korean owner out of the area.

The Rodney King Verdict: The Riots Begin

The other relevant background story is the trial of Rodney King. This was what touched off the LA riots. The short version of the story is that Rodney King led the police on a high-speed chase going up to 115 miles per hour. He was evading them because he was driving while under the influence and was on parole at the time. His two passengers were loaded into the squad car first, with King exiting the car last.

The other relevant background story is the trial of Rodney King. This was what touched off the LA riots. The short version of the story is that Rodney King led the police on a high-speed chase going up to 115 miles per hour. He was evading them because he was driving while under the influence and was on parole at the time. His two passengers were loaded into the squad car first, with King exiting the car last.

King was beaten for approximately two minutes straight on a 12-minute tape recorded by a nearby civilian. He was also tazed. King repeatedly attempted to get up despite instructions to stay down. Officers later testified that they believed he was on PCP at the time, but his toxicology test ruled this out. The tape became a national sensation and then-Chief Daryl Gates described himself as being in “disbelief” when he saw the tape.

Four of the five officers on the scene were charged. The jury, which contrary to popular belief, was not “all white,” but did not include any black members, acquitted the four officers on assault, acquitted three of them on excessive force and resulted in a hung jury on the fourth charge after seven days of deliberation.

At 5 p.m. after the verdicts were announced, Mayor Tom Bradley gave a press conference interpreted by many, including Assistant Los Angeles police chief Bob Vernon, as effectively giving permission to riot. Vernon stated that police incidents increased noticeably after the mayor’s statement.

The event credited with touching off the riots was the arrest of 16-year-old Seandel Daniels at 71st and Normandie in South Central Los Angeles. The rioters began attacking Koreatown on the second full day of rioting.

Koreatown Gets Attacked During 1992 LA Riots

Koreans began moving to Los Angeles in large numbers after the passage of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, a radical departure from previous immigration laws that dramatically changed the demographic character of the nation, including Los Angeles. Many Koreans opened successful businesses in the area, but incurred resentment and racism from black residents, which is documented in popular culture of the time such as Do The Right Thing and Ice Cube’s “Black Korea” off of Death Certificate.

When the riots spread throughout the city, the LAPD blocked roads going through Koreatown into more affluent neighborhoods. This was seen by many residents as a containment that effectively left Koreatown residents trapped inside the riot zone. What’s more, the police and other first responders ignored the pleas for help coming from within Koreatown.

Of the nearly $1 billion in damages done during the riots, over half of it was done to Korean-owned businesses.

Enter the Roof Koreans

The Korean community of Los Angeles did not simply sit by and allow their neighborhood and businesses to be destroyed by rioters without lifting a finger. On the contrary, the images of Korean shopkeepers and their families defending themselves from the rooftops of their buildings soon became one of the most iconic images of the riots. Live footage of gun battles were circulated on cable news and elsewhere. The images still resonate with freedom lovers to this day – what image could be more powerful than an ethnic minority refusing to subject itself to a pogrom, instead taking to the rooftops to defend themselves with deadly force, if necessary?

The Korean community of Los Angeles did not simply sit by and allow their neighborhood and businesses to be destroyed by rioters without lifting a finger. On the contrary, the images of Korean shopkeepers and their families defending themselves from the rooftops of their buildings soon became one of the most iconic images of the riots. Live footage of gun battles were circulated on cable news and elsewhere. The images still resonate with freedom lovers to this day – what image could be more powerful than an ethnic minority refusing to subject itself to a pogrom, instead taking to the rooftops to defend themselves with deadly force, if necessary?

For firearms collectors, the Roof Koreans present another avenue of interest: They used many cool weapons that largely left the market after the Assault Weapons Ban of 1994 was passed. The Intratec TEC-9 and the A.A. Arms Kimel AP-9 are just two of the weapons used by the Roof Koreans, alongside more standard weapons such as the Daewoo K1, standard issue for the Republic of Korea’s military.

The Republic of Korea’s military is another key part of the story with regard to the Roof Koreans. Far from an untrained mob of men who took up with arms sans training, the Roof Koreans were, by virtually any definition, “a well-regulated militia.” Many of them had experience in the South Korean Army, as South Korea has conscription with very few exceptions.

It’s worth noting that virtually every weapon used by the Roof Koreans to defend themselves, their businesses, their communities and their families would be against the law or, at least, highly restricted today. “High capacity magazines” (anything over ten rounds) are against the law and there is a 10-day waiting period for all firearms purchases. As the riots lasted five days, this would have put anyone who had not already purchased a firearm in a seriously precarious position.

The Lessons of the Roof Koreans

Kurt Schlichter was in Inglewood at the time of riots, one of the hardest hit areas. He speaks eloquently on the topic of the Roof Koreans (or “Rooftop Koreans” as he calls them) and the need of communities to defend themselves. His account of defending Los Angeles against riots is worth reading, despite the fact that he was not in Koreatown.

He makes the case that it is not just wise, but the responsibility of all Americans to prepare themselves for such events. And while we would not go as far as him to suggest that people ought to be legally required to prepare for such an event, we do agree with him that everyone is their own first responder. More than that, there is a solid argument to be made that we have a duty to our community to prepare for those times when individual defense is not enough, but a common defense is necessary.

The Roof Koreans provide a perfect, real-life counter argument to the idiotic question of gun grabbers that free men justify why they “need” certain arms to defend themselves. If ever anyone “needed” a fully automatic rifle with a 100-round magazine, it was the Korean community of Los Angeles.

Unsung Heroes

- S.B. Fuller

- Annie Oakley

- Edward Snowden

- Sam Colt

- Davy Crockett

- Susan B. Anthony

- Milton Friedman

- Vaclav Havel

- Charlton Heston

- Sojourner Truth

- Ted Nugent

- Eugene Stoner

- John Garand

- Charles Parker

- Oliver Winchester

- Charles Newton

- Lysander Spooner

- John Moses Browning

- Butch O'Hare

- Georg Luger

- Elmer Keith

- Benjamin Tyler Henry

- Ron Paul

- Witold Pilecki

- Roof Koreans

- Belle Starr

- Carlos Hathcock